Moral and political progress aren't illusions

Liberal democracy is the greatest engine of human progress

Is humanity capable of moral and political progress? This question was at the heart of a recent debate between John Mearsheimer and Steven Pinker, which was framed as a discussion about “The Enlightenment and its alternatives.” Pinker is among the best-known defenders of Enlightenment principles such as humanism and liberalism, and his 2018 book Enlightenment Now is a study of how these principles have built a healthier, more peaceful, and more democratic world. Mearsheimer is an international relations professor at the University of Chicago who takes a much dimmer view of the ideas and institutions produced by the Enlightenment. His book The Great Delusion was published the same year as Enlightenment Now, and it argues that moral and political progress are illusory — a view he returns to in his debate with Pinker.

As I’ve argued in several previous essays, Pinker’s case for human progress is difficult to refute: rates of poverty, war, and mortality from many causes are collapsing while health, education, and wealth have seen drastic and sustained improvement. While Mearsheimer generally acknowledges that material progress has taken place, he believes this has no bearing on whether we’ve improved morally or politically. This is because he demands an impossible standard for demonstrating the reality of such progress. According to Mearsheimer, “The question is: has the Enlightenment created a situation where there is large-scale consensus — almost overwhelming consensus — on questions about first principles, on questions about the good life?” He believes the commitment to “unfettered reason” has only created new and deeper ethical divisions that have no hope of being resolved.

It’s unclear why Mearsheimer believes “overwhelming consensus” is necessary before we can claim that humanity has made moral and political progress. Does the continued practice of slavery in places like Mauritania (where legal slavery wasn’t banned until 1981 and de facto slavery survives to this day) negate its abolition throughout the rest of the world? Does the existence of autocratic states like Russia and China alter the fact that the total number of democracies has surged since the middle of the twentieth century? Mearsheimer claims that some forms of material progress — such as the precipitous decline in infant and child mortality — tell us nothing about moral progress, because saving the lives of children has been regarded as a good thing “since time immemorial.” Pinker counters that there are many practices we regard as abominable today which were considered morally acceptable in the past, like slavery and human sacrifice. While we haven’t escaped other evils like genocide, these crimes invite near-universal moral condemnation and international legal mechanisms (like the Genocide Convention) exist to prevent, halt, or punish them. Many people consider the Bible the highest arbiter of moral truth, but few would embrace its multiple endorsements of genocide and slavery.

Like the material progress that has taken place on an enormous scale, our species’ moral progress is undeniable. What Thomas Jefferson once described as the “execrable commerce” of the slave trade is now illegal everywhere (though the practice persists in some parts of the world). Racial segregation in the United States was a daily reality for millions of people within living memory, but it is now considered one of the country’s greatest sins. Much of the world has stopped systematically preventing women from taking part in the political and economic lives of their societies. One remarkable feature of moral progress in the modern world is how quickly it can take place — while just 27 percent of Americans thought same-sex marriages should be legal in 1996, this proportion surged to over 70 percent 25 years later. The U.S. Supreme Court legalized gay marriage in 2015.

Enlightenment thinkers destroyed the intellectual foundations of moral blights like religious persecution (David Hume, Baruch Spinoza, and Voltaire), cruel and unusual punishment (Cesare Beccaria), and the divine right of kings (John Locke). When Locke argued that the legitimacy of the state must arise from the consent of the governed, he laid the foundation for future democratic republics like the United States. These republics are now among the wealthiest and most stable countries on earth — a reminder that material, moral, and political progress are often inseparable.

Pinker points out that liberal democracy — a political system founded upon the Enlightenment ideals of self-determination, the rule of law, and individual rights — is predicated on the fact that we won’t reach a consensus on ethics and politics. This is a core theme of Francis Fukuyama’s 2022 book Liberalism and Its Discontents — that liberal democracy doesn’t exist to impose some specific idea of the good on all people, but rather creates the space for people to pursue their own ideas about what makes a good life. Fukuyama explains that an essential function of liberal democracy is to “lower the aspirations of politics.” Ideologies such as Marxism, on the other hand, purport to offer comprehensive explanations of society, economics, and politics; provide a rigid teleology which promises some future utopia where all problems are corrected and all contradictions are resolved; and tend to become absolutist tyrannies that can’t tolerate dissent.

Liberal democracy has more modest ambitions — to provide a political framework in which citizens can believe what they want and peacefully compromise on matters of public policy and representation. Nobody gets everything they want, but nobody will be able to force their will on others or violate their rights. While this may not inspire as much fanatical passion as ideologies with grand visions of spiritual fulfilment and ultimate justice, that’s the point. Pluralism is a prerequisite for the long-term health of open and diverse societies, and while the liberal state must be strong enough to enforce the law and maintain security, it must also take a step back in matters of conscience and political preference. The endless state coercion in communist countries led to economic stagnation, political decay, and dissolution, while liberal democratic countries remain the richest, freest, and most desirable places to live.

Democracies tend to be more stable than their authoritarian alternatives, as they impose robust institutional constraints on leaders (through laws, elections, other branches of government, etc.); allow citizens to participate in the political process; protect individual rights (including the rights of minorities); and create a safe and regulated environment for investment, commerce, and property ownership. One of the most debilitating problems for authoritarian systems is a lack of accurate information filtering up to decision-makers. There are too many lackeys who are more concerned with appeasing the party or leader than providing objective assessments of problems confronting the government or how well policies are working. This doesn’t just lead to catastrophes like Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward, Xi Jinping’s zero-COVID campaign, and Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine — it also increases the likelihood that authoritarian leaders will double down on failed policies.

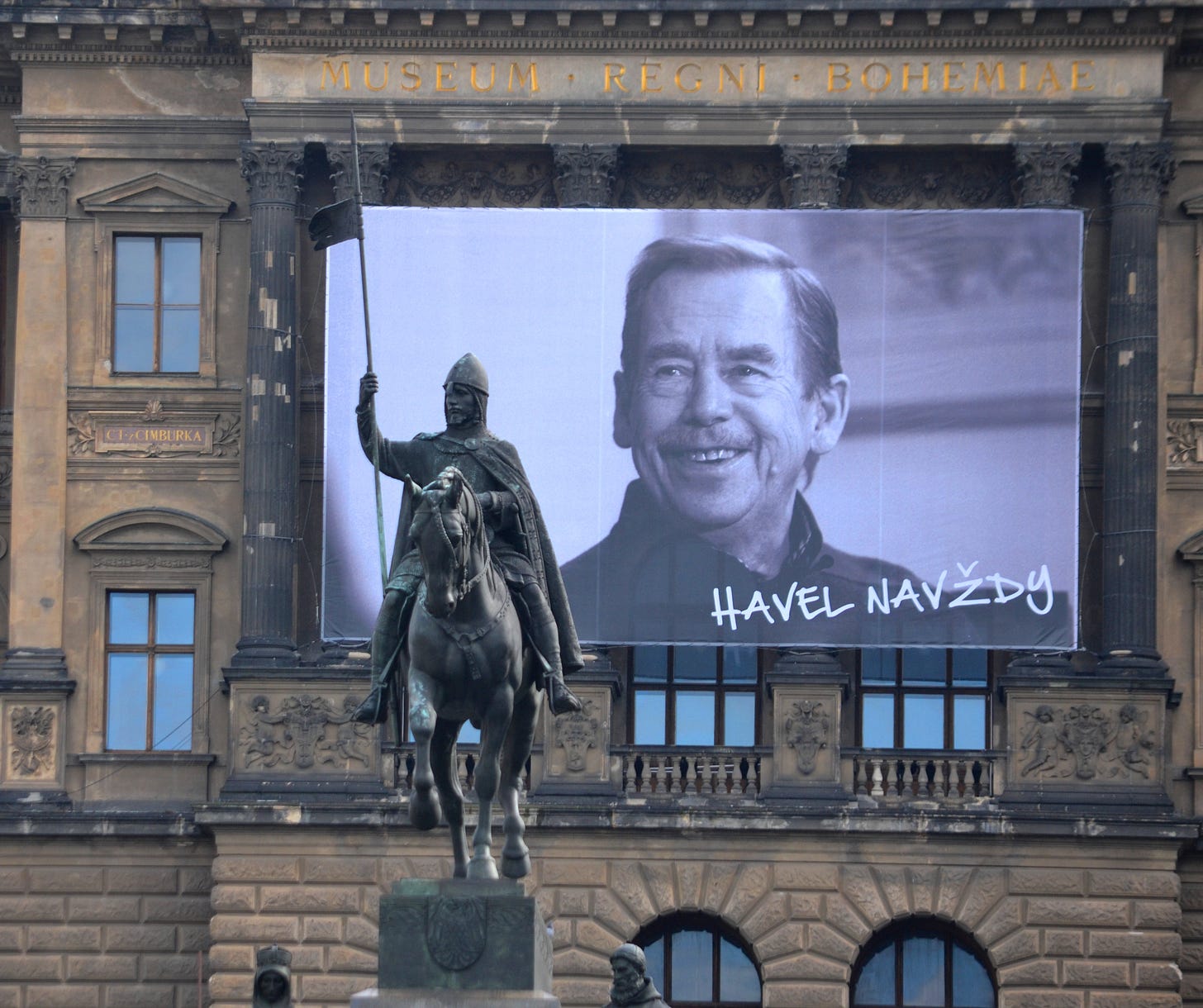

Beyond the practical case for democracy — which has given many states compelling incentives to adopt it — the global democratic transition is a moral revolution. When citizens throughout Eastern Europe organized campaigns of civil resistance, created political parties and activist groups, and took to the streets to demand an end to Soviet oppression, they spoke the moral language of freedom and human rights. In a 1969 letter to Alexander Dubček, Václav Havel declared that the struggle for democracy from behind the Iron Curtain was not hopeless: “Even a purely moral act that has no hope of any immediate and visible political effect can gradually and indirectly, over time, gain in political significance.” Havel was an author, statesman, and one of the most important dissidents in Eastern Europe, whose Civic Forum played an integral role in the overthrow of communism in the Czech Republic (then Czechoslovakia). He was writing to Dubček at a time when the fall of the Soviet Union was still two decades away, but his words would be vindicated in his own lifetime.

Havel never shied from the moral dimension of politics or history. When he delivered a speech commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1998, he argued that the document was more profound than a “mere contract among people who have found it practical to have their rights articulated and guaranteed in some way or other.” Rather, he observed that the declaration is built upon foundational moral principles such as human dignity, which underpin “all the fundamental human rights and human rights documents.” He explained that the declaration could move governments toward “moral order” and foster a “renewed sense of responsibility for this world.” Havel recognized that the declaration was more than an aspirational document, noting that its “imprint is borne by … hundreds of international treaties and constitutional instruments of individual nations.” He also emphasized how the declaration supported the fight for democracy in the USSR:

The emphasis placed in that document on human rights helped to put an end to the bipolar division of the world. It added momentum to the opposition movements in the communist countries who took the accords signed by their governments seriously, and intensified their struggle for the observance of human rights, thus challenging the very essence of totalitarian systems.

Democratic norms and institutions are exportable. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, many new Eastern European democracies learned from existing democracies (and each other) as they liberalized their political systems and economies. Beyond observing common principles in their laws and constitutions, democracies have formed international organizations which require members to observe specific requirements around elections, the rule of law, and human rights. For example, the EU imposes standards for democratic accountability on all members, and its founding document formalizes the “general objective of developing and consolidating democracy and the rule of law, and … of respecting human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Prospective members of the EU must demonstrate that they share these objectives, while existing members can be sanctioned for failing to do so.

Brussels has withheld tens of billions in EU funds for Hungary over concerns about judicial independence, academic freedom, state-sanctioned homophobia, and the human rights of asylum seekers. Ukraine became a candidate member of the EU in June 2022, and Kyiv is attempting to meet the union’s requirements on corruption, human rights, and other issues. A recent survey found that 92 percent of Ukrainians want their country to become a member state of the EU by 2030. The desire for greater political and economic integration with Europe is what launched the Euromaidan protests in 2013. These protests led to the ouster of the Moscow-backed President Viktor Yanukovych — who had rejected an association agreement between the EU and Ukraine in favor of closer ties to Russia, which infuriated many Ukrainians. Russia’s annexation of Crimea, war in Donbas, and eventual invasion of the entire country followed. Putin fears the emergence of a successful, integrated European democracy next door, which is why he’s waging war on Ukraine.

Just as Havel and many other dissidents fought for democracy and dignity during the Cold War, Ukraine is fighting for these rights today. One reason so much of the world has gravitated toward democracy is the innate yearning for freedom — a yearning that is expressed across many cultures and geographies, from the battlefields of Ukraine to the streets of Hong Kong and Tehran. While it’s true that liberal democracy seeks to lower the aspirations of politics, this seemingly modest goal has been one of the great engines of political change over the past three-quarters of a century.

For most of human history, rights were reserved for certain classes, races, members of religious groups, and so on. This is why the liberal concept of universal human rights is revolutionary — it elevates rational arguments for social and political equality (many of which trace their intellectual lineage to the Enlightenment) over the tribalism that comes so naturally to human beings. Liberal democratic governments recognize that the best way to secure this equality is to protect the individual rights of all citizens — a concept Mearsheimer struggles to understand. He observes that

Radical individualism is associated with the Enlightenment. My view is that human beings are social animals to begin with, who carve out room for their individualism. But because they’re social animals to begin with, human beings belong to tribes. Today, we call them nations.

Mearsheimer connects this observation to his first point about the lack of moral and political consensus by arguing that nations are collective embodiments of irreconcilable worldviews. He is, of course, correct that human beings are social animals. But while it may be true that our instinctive tribalism is most clearly expressed in our national commitments today, such large-scale cooperation is a relatively recent development in our evolutionary history. There was a time when tribalism didn’t extend beyond, well, the tribe. The shift from tribal societies to dynamic and complex nations spanning thousands of miles and encompassing hundreds of millions of people suggests that human beings are capable of drastically expanding their sense of tribal solidarity.

This solidarity can extend beyond national borders — during the 2016 referendum on Britain’s membership in the EU, many Britons took to the streets waving EU flags and expressing their desire to remain part of the union. They declared that their identities as citizens of the United Kingdom were bound up with their identities as Europeans, and a substantial majority now believe Brexit was a mistake.

One reason the United States and many European countries have provided significant economic, military, and humanitarian support to Ukraine is their affinity with a fellow democracy under siege — a democracy which seeks to join the liberal West. While liberal democracies have distinct histories and cultures, they also share many fundamental values and institutions. This leads to trust and a sense of shared purpose, especially when these values are integral to international institutions like the EU and NATO — perhaps the most successful military alliance in history, which restrained Soviet aggression during the Cold War and maintained peaceful relations between major European democracies for 75 years.

In The Great Delusion, Mearsheimer argues that “nationalism and realism almost always trump liberalism.” In other words, he believes people are more devoted to their nations than abstract liberal values like democracy and individual rights. Because nations have so much destructive power, their clashing values will cause interminable conflict. One reason Mearsheimer can’t acknowledge the reality of large-scale moral and political progress is his devotion to a theory of international relations called realism. Realists have an extremely reductionistic and mechanical view of the relationships between states — they believe state behavior has very little to do with political systems, national histories, ideologies, values, the personalities of leaders, or any other internal characteristic. Rather, all states behave according to a simple calculation: how much power they have relative to other states. If a state is more powerful than its neighbors, it will seek to dominate them. If a state is less powerful, it will form alliances and seek to tilt the balance of power in its favor.

According to realism, because Germany is the strongest state in Western Europe, it should seek regional hegemony. In fact, this is exactly what Mearsheimer predicted would happen at the end of the Cold War. He expected NATO to disband as the Soviet threat receded — NATO drastically expanded instead — and he thought this would lead Germany to build a nuclear arsenal and threaten its neighbors. “Germany would no doubt feel insecure without nuclear weapons,” he wrote in a 1990 essay, “and if it felt insecure its impressive conventional strength would give it a significant capacity to disturb the tranquility of Europe.” Once NATO disappeared and the “Germans are left to provide for their own security,” Mearsheimer speculated: “Is it not possible that they would countenance a conventional war against a substantially weaker Eastern European state to enhance their position vis-a-vis the Soviet Union?” He even lamented the fact that Eastern European states would refuse to cooperate with Moscow to “deter possible German aggression.” Imagine a world in which Vladimir Putin was forced to prevent Angela Merkel or Olaf Scholz from conquering Germany’s neighbors, and you’ll see how completely realism failed to predict what would happen after the Cold War.

Like all realists, Mearsheimer doesn’t understand that the internal characteristics of states have a huge impact on their actions. The historical memories of World War II and the Holocaust have made Germany’s political culture far less militaristic and more focused on integration than Russia’s. This is why Berlin is the anchor of the EU while Moscow is an international pariah that invades its neighbors and spurns the liberal international order. Like other Western European democracies, Germany is more interested in economic growth and peaceful cooperation with its neighbors than territorial aggrandizement.

But the more fundamental problem with Mearsheimer’s analysis is his refusal to acknowledge moral and political progress. Despite what realists may think, there’s no iron law of the universe that forces states into a permanent state of mutual suspicion and hostility. Alliances and partnerships between liberal democracies aren’t merely transactional — they revolve around a shared commitment to liberal values. As Germany builds up its military to confront Russian aggression, we aren’t going to see France fortifying its eastern border (which is what realists insist should happen). Instead, the United States and other European countries will continue to welcome a more powerful Germany as a counterweight to the increasingly dangerous totalitarian states to the east.

Mearsheimer doesn’t just misunderstand how the mutual commitment to liberalism forges stronger bonds between countries — he misunderstands liberalism itself. Recall his argument that nationalism “trumps” liberalism. This view is based on his belief that “nationalism is more in sync with human nature than liberalism, which mistakenly treats individuals as utility maximizers who worry only about their own welfare rather than as intensely social beings.” He continues:

The taproot of the problem is liberalism’s radical individualism and its emphasis on utility maximization. It places virtually no emphasis on the importance of fostering a sense of community and caring about fellow citizens. Instead, everyone is encouraged to pursue his own self-interest, based on the assumption that the sum of all individuals’ selfish behavior will be the common good.

This isn’t even a caricature of liberalism — it’s a total misunderstanding of the concept. Liberalism isn’t some extreme form of libertarianism which privileges self-interest over social solidarity. While there are liberal arguments for economic freedom, there are also liberal arguments for constraining the free market in the name of the common good (with regulations that limit pollution and other externalities, for instance). Over the past 60 years, the proportion of GDP dedicated to social spending has increased substantially in every major liberal democracy — a reflection of the liberal commitment to equality and social solidarity.

John Rawls is one of the most influential liberal thinkers of the past century, and he urges us to consider the type of society we would build from behind a “veil of ignorance” — with no knowledge of our economic circumstances, social position, identity, physical characteristics, etc. This isn’t an endorsement of selfish individual utility maximization — it’s a demand for fairness and equality, or at least what Rawls describes as an “equal right to the most extensive system of equal basic liberty compatible with a similar system for all.” This liberty doesn’t just include the freedom to pursue one’s own self-interest — it also means freedom from, say, poverty and other forces that prevent people from flourishing.

Egalitarianism is central to liberal thought, which is why many liberals would reject Mearsheimer’s notion that liberalism increases social atomization and selfishness to secure the common good. While Mearsheimer’s understanding of liberalism is constricted and unfair, his understanding of nationalism is strangely indulgent. If it’s true that nationalism fosters a “sense of community and caring about fellow citizens,” why are so many nationalists prejudiced toward immigrants, members of minority religions, and other fellow citizens who don’t fit their essentialized notions about national identity? It’s often liberals who resist this sort of bigotry with arguments about the importance of fairness and an inclusive sense of national identity.

In liberal democracies, citizens have the legal and institutional resources they need to fight for moral and political change. While Mearsheimer believes individualism is a source of social stratification, the demand for individual rights has been central to many of the most important political movements throughout history. Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement argued that all Americans should be treated as equal individuals under the law, rather than members of favored and oppressed racial groups. Does the success of the Civil Rights Movement constitute evidence of moral and political progress for Mearsheimer? If the answer to this question is “no,” it’s difficult to understand what could possibly meet his exacting standards — perhaps world peace or the total and permanent elimination of racial prejudice everywhere on earth overnight.

The debate between Pinker and Mearsheimer isn’t just an abstract academic dispute. The refusal to acknowledge moral and political progress is one of the gravest threats to liberal democracy, as it undermines already-low confidence in democratic institutions, allows autocratic leaders to declare their moral and political superiority, and fuels a growing sense of despair and civic disengagement. At a time when illiberal populist movements like nationalist authoritarianism remain powerful forces in Western democracies, defenders of liberal democracy must restate their case more forcefully than ever. Anti-democratic demagogues like Donald Trump insist that American democracy is irredeemably corrupt and ineffective because he wants to dismantle the democratic safeguards that held him in check during his first term. Meanwhile, Trump argues that the liberal international order is a scam and a failure because he wants to destroy that, too.

There’s a reason nationalist authoritarian leaders like Trump’s friend Viktor Orbán are big fans of Mearsheimer — he provides an intellectual ballast to their illiberalism. “The liberals have got it all wrong,” Orbán announced after a November 2022 meeting with Mearsheimer, “that’s the bottom-line of our great conversation with Prof Mearsheimer today.” The subtitle of The Great Delusion is “Liberal Dreams and International Realities.” Mearsheimer thinks of himself as a realist both in the narrow academic sense and the broader colloquial sense. He believes it’s prudent to assert that the appeal of Enlightenment liberalism will always be limited (despite the dramatic growth of this appeal over the centuries). He thinks states are motivated by power alone, not values. He expects human beings to remain mired in a permanent state of zero-sum competition forever.

But there’s nothing realistic about these beliefs. Moral and political progress are indisputable facts, and they have been secured on a vast scale by the spread of liberal democracy around the world. While we will continue to face democratic recessions, nationalist revolts, and totalitarian aggression, the liberal democratic idea is resilient. It has survived civil war, fascism, communism, and many greater challenges than the ones it faces today. It has taken root in parts of the world that were supposed to be uniquely resistant to it. And it has secured greater freedom, wealth, and human flourishing than any of its alternatives. The liberal ideas and institutions which originated in the minds of a few Enlightenment thinkers several hundred years ago have become the most powerful political forces on earth, and the stubborn denial of this fact doesn’t make it any less true.