Part I: The triumph of the liberal international order

Reviewing 75 years of global convergence

Note: This is the first essay in a three-part series about the liberal international order and the forces trying to dismantle it. Look for part II next week.

I was born a few months before the fall of the Berlin Wall. Francis Fukuyama had just published “The End of History?” in The National Interest. The Soviet Union would officially dissolve within two and a half years. A powerful sense of optimism about the possibilities of a post-Cold War world would soon sweep through many democratic capitals — and the capitals of several democracies-to-be.

Intelligence agencies and Sovietologists puzzled over how quickly and completely the USSR collapsed. In 1991, former CIA director Stansfield Turner admitted that it would be a mistake to “gloss over the enormity of this failure to forecast the magnitude of the Soviet crisis.” A relatively peaceful end to the Cold War was far from inevitable, as the Soviet Union controlled the largest authoritarian security apparatus and nuclear stockpile on earth. But Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms and the demand for sovereignty from newly empowered parliaments across Eastern Europe — which were already running de facto independent states — made this outcome unavoidable.

Less than two years after the fall of the wall, the United States took its own nuclear bombers and ICBMs off alert and successfully negotiated major arms control treaties with its longtime adversary. In September 1991 — a few months after the negotiation of the landmark START I treaty — President George H.W. Bush unilaterally authorized a significant reduction in the United States’ deployed tactical nuclear weapons. A week later, Gorbachev responded in kind by removing or destroying a substantial number of weapons and launch systems. These moves came as global inventories of nuclear warheads were beginning a precipitous decline — from a peak of over 70,000 in the mid-1980s to around 12,500 today. The horrible logic of mutually assured destruction had evolved into mutually assured de-escalation.

The final decade of the twentieth century looked surprisingly promising — it wasn’t a bad time to enter the world. As the threat of nuclear apocalypse waned, Bush heralded the arrival of a “New World Order.” In a 1990 speech, he said this order would bring about a “world quite different from the one we’ve known. A world where the rule of law supplants the rule of the jungle. A world in which nations recognize the shared responsibility for freedom and justice.” Bush and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher even touted what they described as a “peace dividend” — the idea that reductions in military spending would lead to social and economic benefits. International trade and cooperation accelerated, while global poverty plummeted. With the Iron Curtain open and globalization on the rise, it seemed like a matter of time before other authoritarian systems (such as China) liberalized or even democratized. In an October 1997 speech, President Bill Clinton expressed his aspirations for the future of China’s relationship with the United States and the world:

At the dawn of the new century, China stands at a crossroads. The direction China takes toward cooperation or conflict will profoundly affect Asia, America, and the world for decades. The emergence of a China as a power that is stable, open, and non-aggressive, that embraces free markets, political pluralism, and the rule of law, that works with us to build a secure international order — that kind of China, rather than a China turned inward and confrontational, is deeply in the interests of the American people.

The emergence of that kind of China would have been in the interests of the Chinese people and the rest of the world as well, but it was not to be. Some of the loftiest hopes for the post-Cold War world weren’t realized, which is why it’s now fashionable to say the optimism after 1989 was naive and arrogant. But this pessimistic view fails to account for the enormity of the political and economic shifts that took place at the end of the Cold War. In the decade following 1989, the proportion of the world’s population living in some form of democracy rose from less than 39 percent to almost 54 percent. The Maastricht Treaty took effect in 1993 and established the modern EU. At the time, there were 12 members — a number that would rise to 28 within two decades (now 27 after Britain’s departure). NATO membership almost doubled over the same period, including many former Soviet states.

The post-Cold War era has seen historically unprecedented global integration and democratic consolidation. Meanwhile, global economic progress has been rapid and pronounced, largely due to liberal market reforms and rising international trade. For example, trade as a proportion of global GDP increased from 37 percent in 1989 to almost 57 percent in 2021. Over the same period, global GDP per capita jumped more than three-fold. Between 1990 and 2019, the share of people living in extreme poverty (currently defined as less than $2.15 per day) collapsed from almost 38 percent to around 8 percent — from 2 billion people to 648 million (despite a global population increase from 5.32 billion to 7.76 billion). China’s march out of poverty has been particularly remarkable — around 72 percent of the population lived in extreme poverty in 1990, but this proportion tumbled to 0.14 percent by 2019 (the Chinese population grew from 1.15 billion to 1.42 billion over the same period). The era of “Western hegemony,” as the Chinese government describes it, has coincided with the greatest improvement in living standards in Chinese history.

This isn’t to say the West is responsible for China’s economic success. It’s an acknowledgment that China’s shift toward a Western-style market-based economy (albeit one with a high level of state involvement) played a major role in its economic turnaround. The same is true of the East Asian economic miracle, which demonstrated that Japanese and Korean businesses weren’t just capable of competing with their Western counterparts, but of outperforming them. Postwar political development in East Asia was no less of a miracle — Japan built a consolidated modern state in just over a decade (a process which took hundreds of years in Europe), including an extremely effective centralized administrative bureaucracy. The democratization, economic development, and U.S.-led security architecture in East Asia demonstrate the success of the liberal international order just as well as the political and economic integration of Europe.

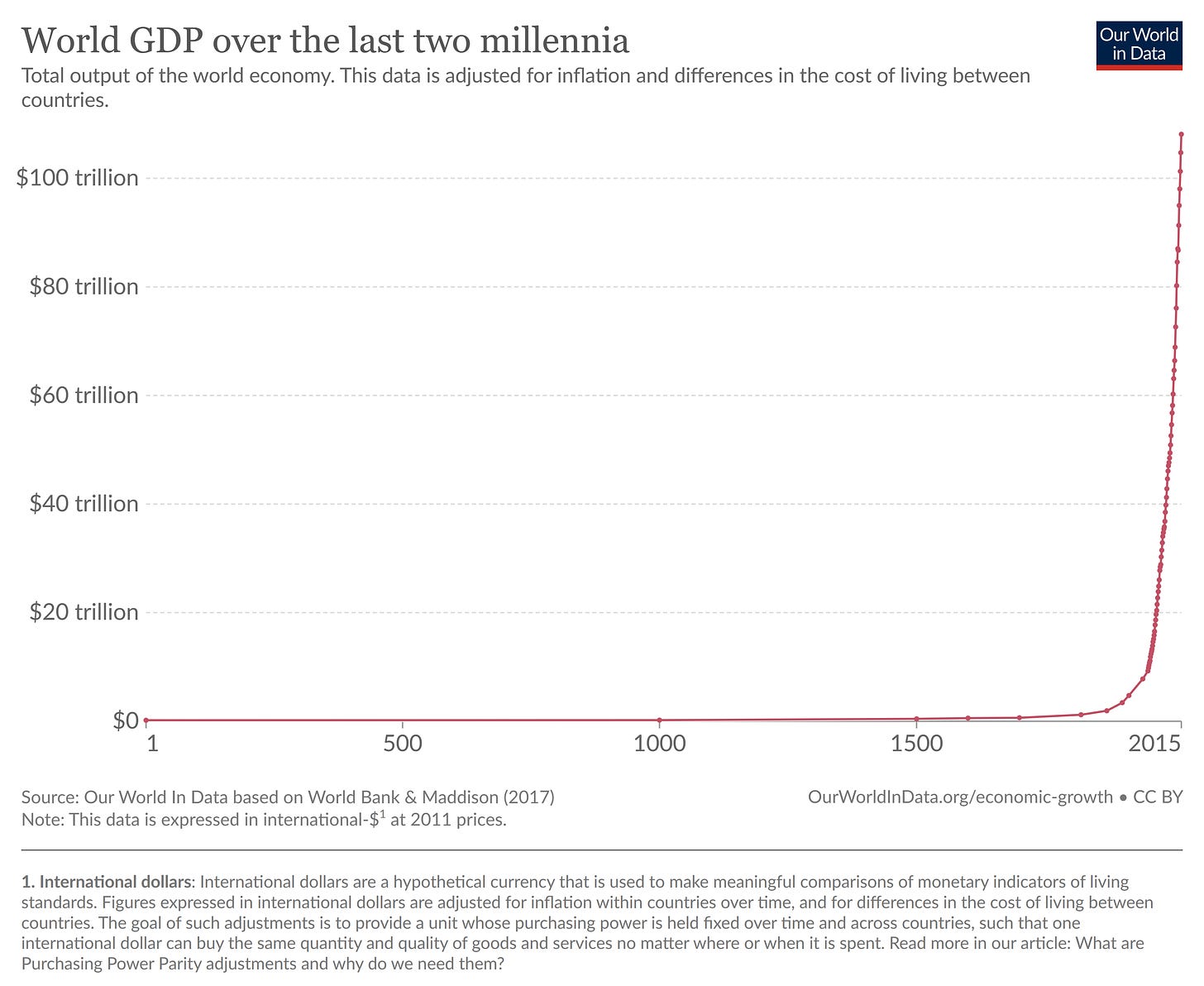

Of course, the explosion in global wealth and human well-being didn’t begin in 1989. Perhaps the most inspiring graph ever produced is this one (published by Our World in Data) which tracks global GDP over the past 2,000 years:

For 1,700 years, the graph is essentially flat until it finally begins to rise significantly with the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth century. Between 1900 and 2015, global GDP increased more than 31-fold, but most of these gains took place after World War II. From 1950 to 2015 — the era of what is often described as the postwar international order — global GDP rose from $9.25 trillion to over $108 trillion. This massive growth in economic productivity hasn’t just benefited wealthy countries in the West. Beyond the almost five-fold decrease in extreme poverty around the world, every major region has seen a substantial rise in GDP (overall and per capita). And none of these measures capture the dramatic increases in the quality of goods and services people can buy with their growing wealth, as well as the availability of products (from smartphones to labor-saving appliances) that didn’t even exist just a few decades ago.

Globalization has been a powerful engine of productivity, innovation, and human well-being. It has enabled hundreds of millions of workers to transition from subsistence agriculture to much better-paying urban jobs, while drastically reducing prices for consumers. It has allowed people, goods, and ideas to move more freely across national borders. It has universalized standards for human rights, good governance, and state behavior. And this is just the briefest glimpse at the benefits of a more interconnected world — the age of globalization may as well be thought of as the age of human flourishing:

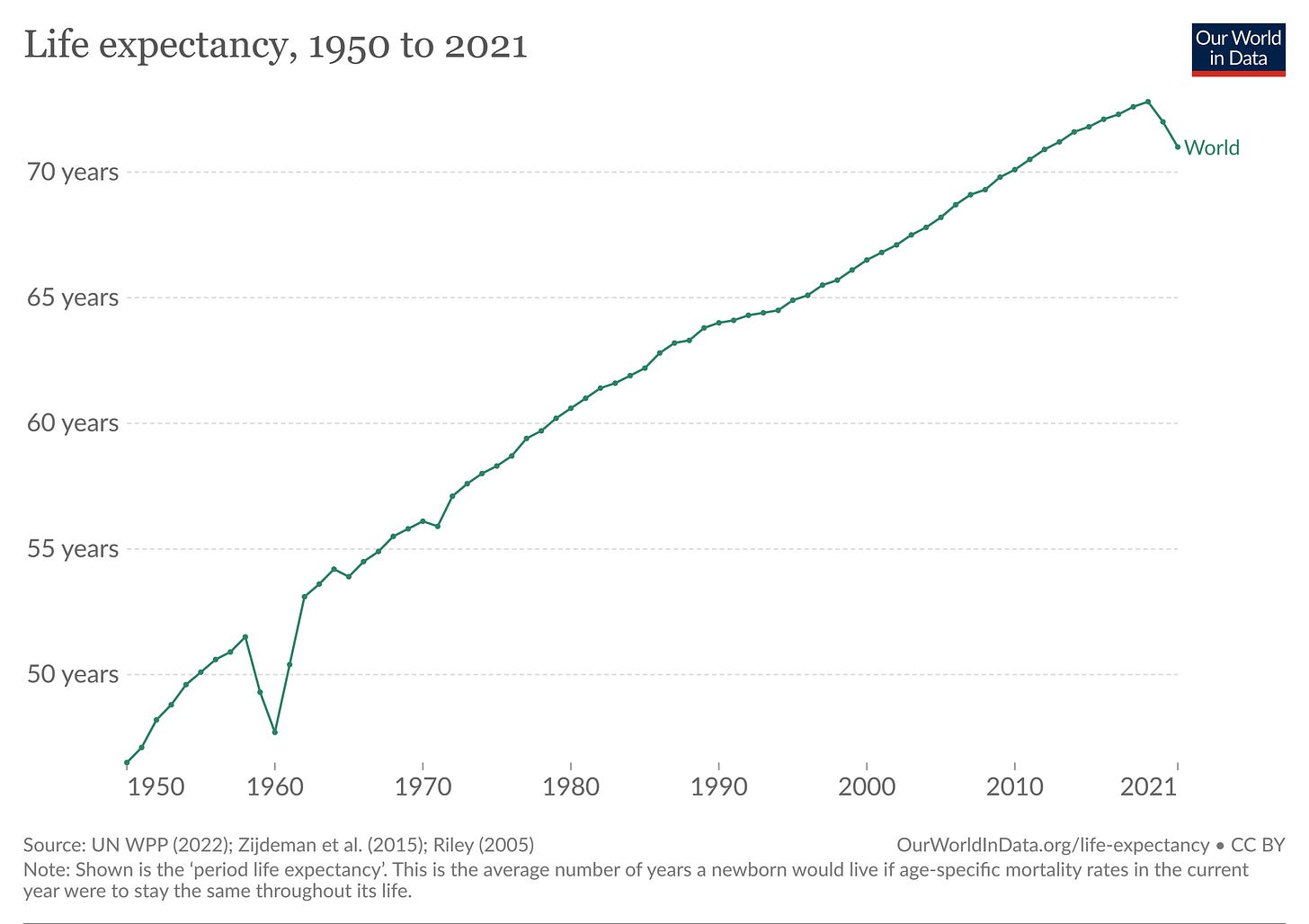

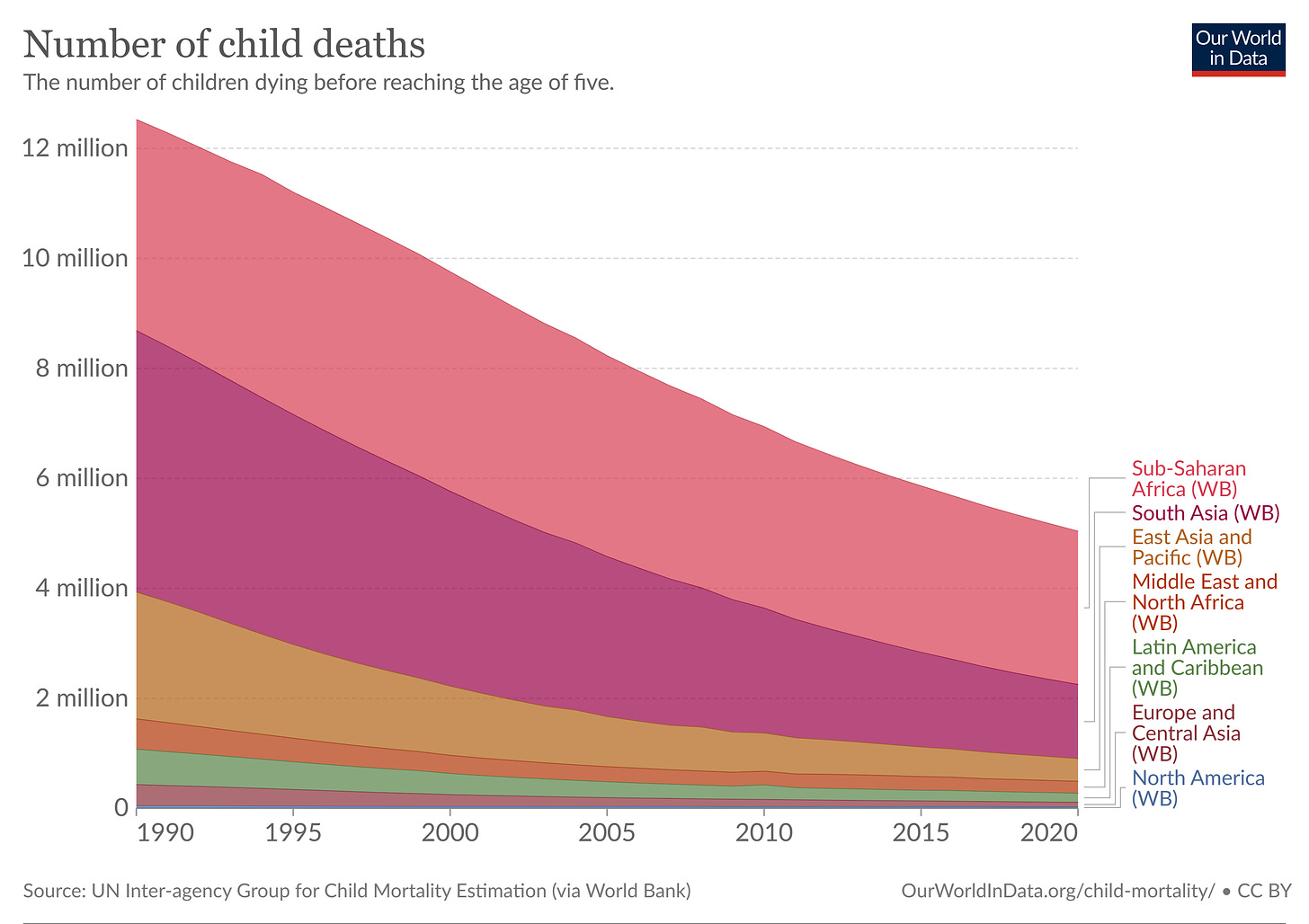

Since 1950, global life expectancy has risen from 46.5 years to 71 years (COVID-19 appears to have caused the largest downtick in over 60 years), while child and infant mortality are lower than ever. In 1950, there was a 27 percent chance that a child would not reach puberty — a proportion that fell to just over 4 percent by 2020. In 1990, almost 13 million children were still dying before the age of five each year, but this number has steadily fallen to just over 5 million (despite global population growth). Maternal mortality has plunged as well.

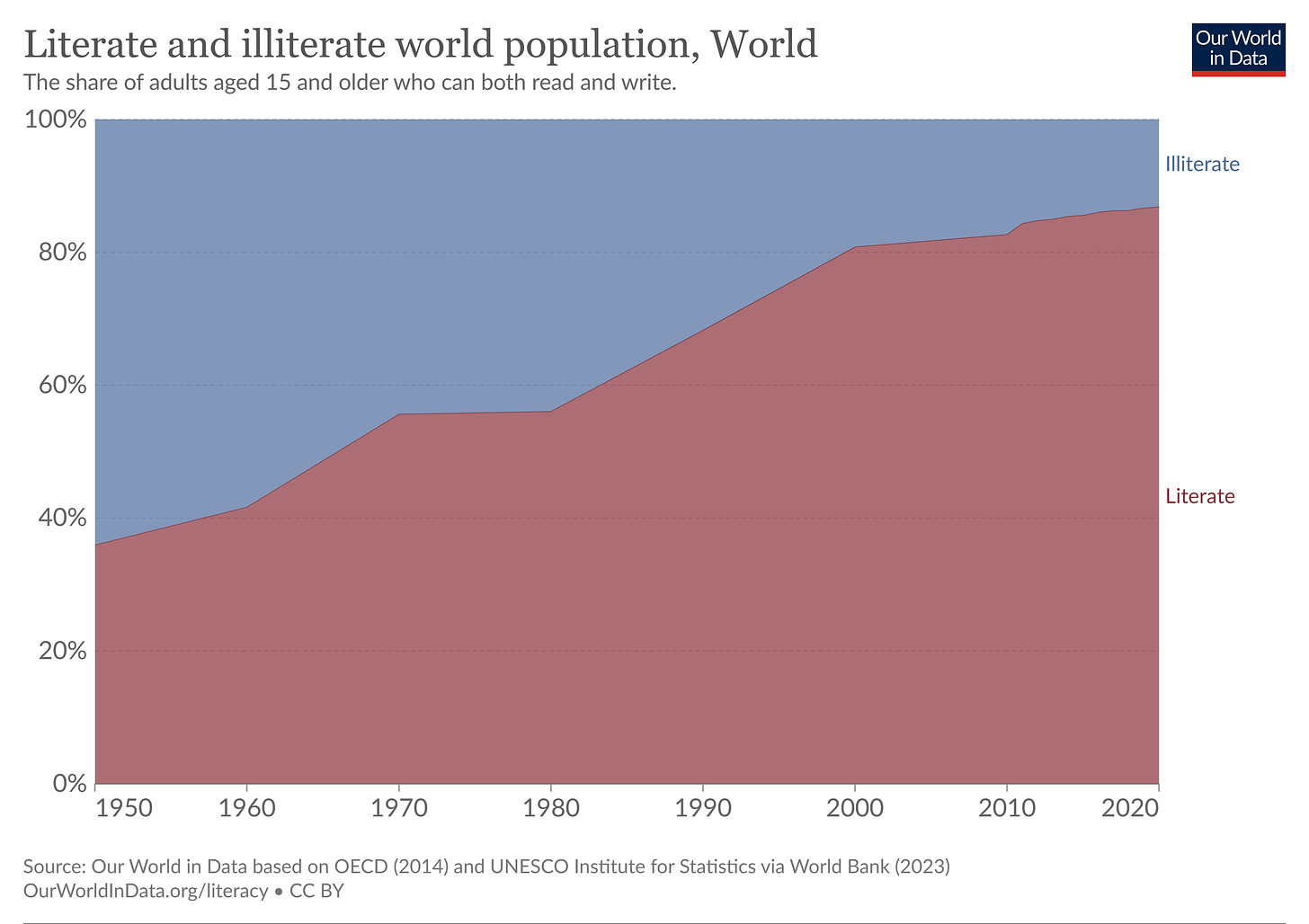

Consider the prospects for children born today versus 75 years ago: beyond the far greater chance that they will survive their first few years, it’s much less likely that they will be forced to work and more likely that they will receive an education. In 1950, the average child could expect to receive just over three years of schooling — a number that had almost tripled to 8.5 by 2015. While just 36 percent of the world’s population was literate in 1950, this proportion is now 87 percent.

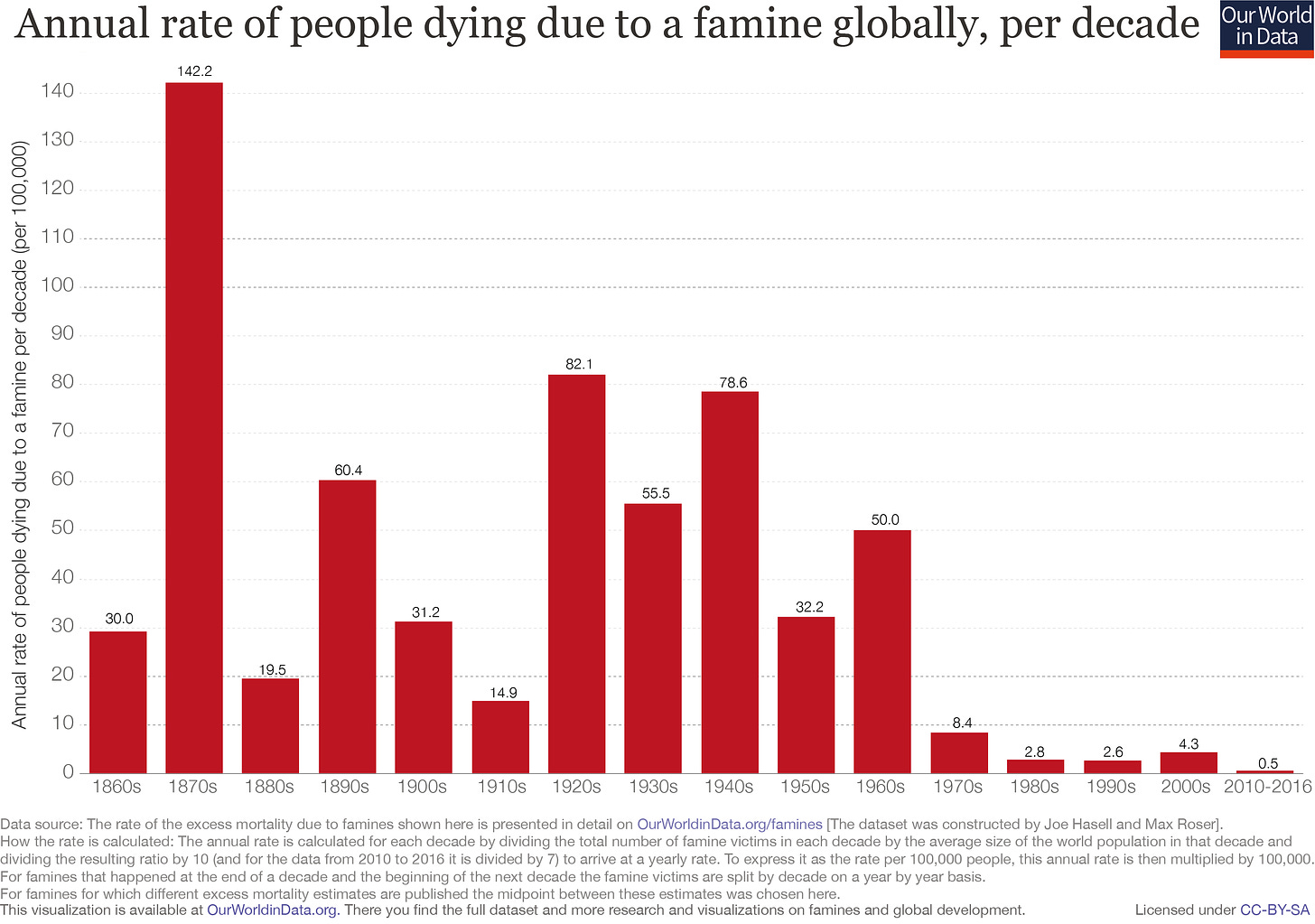

As global wealth has soared, inequality has declined. While inequality has risen in some rich countries like the United States, incomes in many “developing” countries have grown at a faster rate than incomes in their “developed” counterparts (which is one of the reasons the developing-developed dichotomy makes less and less sense). As this economic abundance becomes more widely available, the global division of labor becomes increasingly efficient, and technology around transportation, storage, production, etc. continues to improve, many of our species’ oldest enemies (such as famines) may not be long for this world. While food insecurity remains a major global issue and famines still occur (in North Korea, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan, for instance), the improvement over the past 75 years is unmatched in human history. Paul Ehrlich’s infamous “population bomb” — a thesis which assumed that global population growth would inevitably outstrip food production — never detonated.

This was a short but hopefully instructive tour of progress over the past three-quarters of a century — a single human lifetime. For a more complete picture of just how fundamental and widespread this progress has been, read Steven Pinker’s 2018 book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. A key theme of Enlightenment Now is the necessity of what Pinker describes as “norms and institutions that channel parochial interests into universal benefits.” Robert Wright’s Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny (1999) makes a similar case. There are many ways we can secure our own interests while making the wider international community better off: mutual security arrangements; cross-border commerce that increases wealth for everyone (if unevenly); and cooperation on global threats like climate change, nuclear proliferation, and pandemic preparedness.

The political achievements of the liberal international order may be even more impressive than the social and economic achievements. The idea that a unified Germany would become the anchor of the EU while a democratic Japan would be a vital ally and trading partner under the American security umbrella for three quarters of a century would have exceeded even the most daring ambitions at the end of World War II. Consider what a triumph it is that the thought of a war between Germany and France is unthinkable today — or that the democratic world is urging Germany to build up its military and assume a larger role in European security.

The existence of a peaceful, interconnected Europe — which permits the free flow of people and goods across borders, and which is united under a common currency — was once a radical dream, but it’s now a reality. There are plenty of problems with this project: the difficulty of developing monetary policy among 20 sovereign governments, political instability caused by immigration, a “democracy deficit” due to opaque and bureaucratic decision-making procedures in the EU, the rise of populist authoritarianism in member states like Hungary, and so on. We’ll discuss these issues (as well as how they’ve been cynically instrumentalized by populists and nationalists) in subsequent essays. But the problems with the liberal international order don’t even come close to offsetting the benefits, and many of these problems are unavoidable and manageable byproducts of globalization.

Fukuyama’s End of History thesis has been vilified as the definitive example of post-Cold War hubris for decades. Critics point to the September 11 attacks, the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the Great Recession, civil wars in Libya and Syria, the election of Trump, Brexit, the rise of China, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine as evidence that history continues apace in the twenty-first century. But these critics misunderstand Fukuyama’s argument, which makes no claim about the end of wars, recessions, and global crises. Fukuyama’s central argument is that liberal democracy and capitalism have proven to be more resilient than any of the alternatives — a thesis that is even more plausible today than it was in 1989.

It’s unpopular to say so in an era of anti-establishment populism and resurgent nationalism, but the liberal international order has been a profound success — from the reconstruction of Western Europe after World War II to the victory over the Soviet Union to the expansion of democracy and economic prosperity in the post-Cold War era. In a 2016 speech, President Barack Obama observed: “If you had to be born at any time in human history, it would be right now.” One phenomenon we’ll explore in future essays is the indignant resistance to this view, even among younger generations who have inherited a world that their ancestors couldn’t have imagined. But Obama was right: to be born in a liberal democracy in 2016 (or 1989, for that matter) is a gift that the vast majority of human beings who’ve lived on this planet would gladly have accepted over their own impoverished and violent places and eras. We should save our outrage for the demagogues and dictators who are trying to drag us back to a world that was more divided and less free.

Our species has been doing something right over the past three-quarters of a century, and we should take a closer look at what that is.

It’s good to be reminded of where the global world has come from to serve as a beacon to where we should be and are going. But that beacon can only be as strong as it should be if civilization strives for and believes in the truth, not the convoluted half truths, half fantasies many are pushing around the world ( i.e. Putin, Orban, Trump, etc.). I look forward to reading the remaking essays.

I agree that people often misread Fukuyama, but I found your analysis to be somewhat one-dimensional. Hopefully, the rest of the series will shed more light on the complexity of global history.

My main issue with Fukuyama's and also Huntington's arguments, ("The Clash of Civilizations") is their one-dimensional and linear nature. Globalisation, especially when examined within the broader context of global history, or what is often referred to as "the long duree," reveals its multidimensional nature with various trajectories. Recent global events, such as 9/11, Brexit, and the migration crisis, underscore that globalisation is not a linear process but a complex interplay of different forces and voices. Therefore, it is crucial to move beyond narrow lenses (such as progress and GPD) and recognise the need for a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of globalisation. This perspective respects the dignity of difference, promotes dialogue, and challenges policies that impose perpetuate unequal power dynamics.

Globalisation is not a constant like gravity or the speed of light (can't remember who said this) --

instead, it has undergone radical changes in the past and is likely to do so in the future.