Trump and America's crisis of trust

How Trump exploits and cultivates distrust to increase his power

During a recent leader worship roundtable at the White House—what used to be known as a Cabinet meeting—Attorney General Pam Bondi gushed to Trump: “Your first one hundred days has far exceeded that of any other presidency in this country, ever. Ever. Never seen anything like it. Thank you.” Bondi went on to claim that the Trump administration’s seizure of fentanyl at the border has “saved—are you ready for this, media?—258 million lives.” The media was not, in fact, ready for the attorney general of the United States to make up a cartoonish figure in the middle of a speech so obsequious and propagandistic that it would have made Stalin blush.

If it was true that three-quarters of the country would be dead but for Trump’s peerless leadership, Bondi’s cringing salute at the start of her speech would have made some sense. But it wasn’t true. Nor was HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s claim that the agency he now runs was the “principal vector in this country for child trafficking … during the Biden administration, HHS became a collaborator in child trafficking for sex and for slavery.” A deranged declaration like this made by the nation’s top public health official in a Cabinet meeting would once have been front-page news, but it’s now just one more piece of brazen disinformation pumped into the polluted atmosphere of the Trump 2.0 media ecosystem.

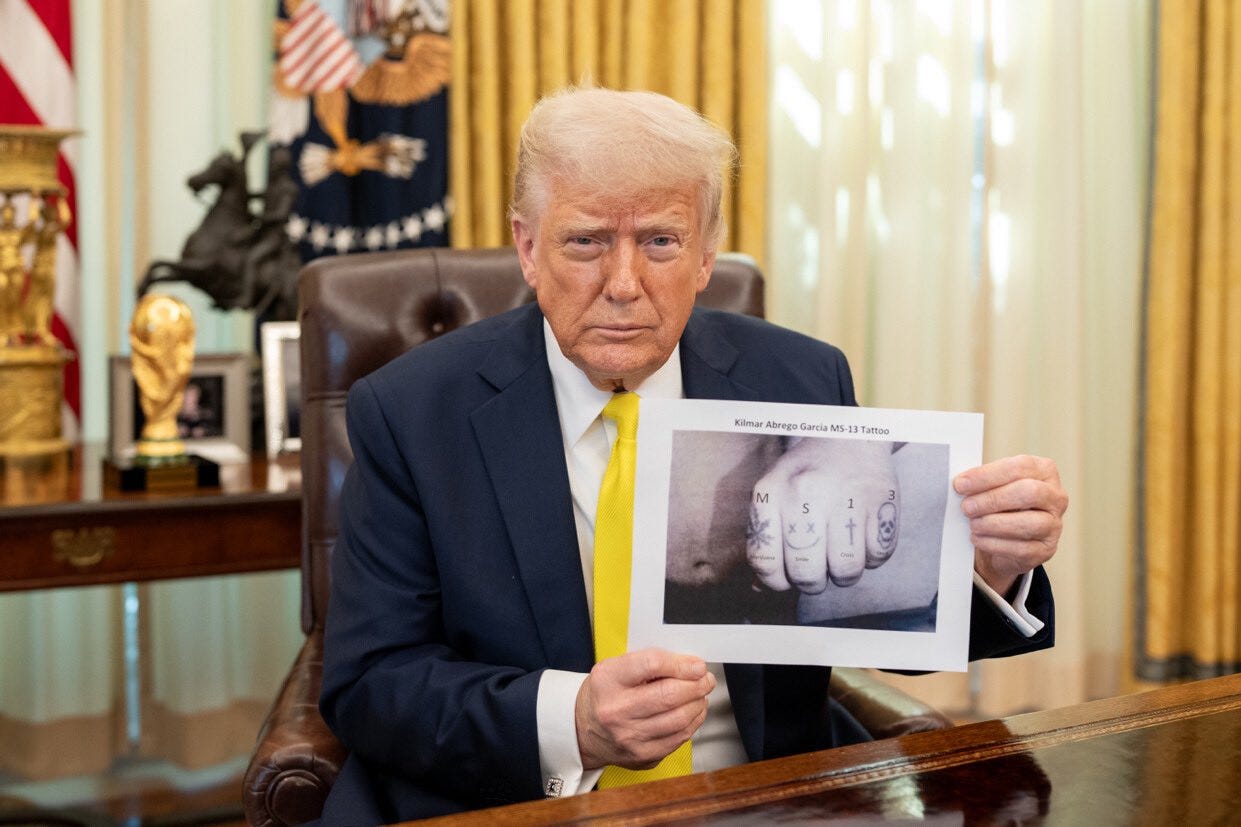

Trump administration officials feel emboldened to disseminate naked falsehoods because they’re taking their cues from the boss. A few days before the Cabinet meeting, Trump told an ABC news reporter that Kilmar Abrego Garcia—who his administration sent to a prison in El Salvador in contravention of a specific court injunction—has “MS-13” tattooed to his knuckles. He was referring to a digitally altered image he held up for the cameras in the Oval Office, in which the letters and digits had been crudely superimposed on Garcia’s fingers to prove he’s a member of the gang. As the interviewer tried to move on to a different subject, Trump spent two minutes insisting that the tattoos are real and triumphantly declaring that he had exposed the media’s lies: “He had M-S, as clear as you can be. … This is why people no longer believe the news because it’s fake news.”

This was a disturbing example of how Trump creates his own reality to generate distrust in the media and other institutions that hold him accountable. The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the Trump administration must “facilitate” Garcia’s return, but administration officials are instead deliberately misreading the decision and attempting to prove that Garcia is a criminal who deserves to be locked up. This is an extraordinary use of propaganda to mask a dangerous arrogation of power by the executive branch. The Trump administration is insisting that it has the right to unilaterally override an existing court order and ignore a Supreme Court ruling all in the service of condemning a man to indefinite detention in a foreign prison with no due process.

Trump thrives in an environment of deep social and political distrust. This is why he actively seeks to undermine trust of all kinds—in experts, the media, courts, and any institution that could serve as a check on his power. He has deputized Elon Musk to destroy trust in the professionalized and nonpartisan civil service so he can fire government employees at will and install sycophants in their place. He has relentlessly undermined trust in the courts because he wants to dismiss any judicial ruling that doesn’t go his way as illegitimate. Trump has even tried to erode trust in the Federal Reserve in an effort to coerce it into cutting interest rates. After he demanded rate cuts in 2018, he said his “gut” is more capable of formulating monetary policy than the Federal Open Market Committee. Trump recently sent markets reeling when he threatened to fire Fed Chair Jerome Powell, which would eliminate the norm of Fed independence—a vital element of global financial stability.

Trump has built his entire political career on distrust.1 His longest-held political position is an intense distrust of the United States’ allies and trading partners, which he believes have been “screwing” the country at every available opportunity. Distrust is a natural byproduct of Trump’s zero-sum worldview, which evaluates every relationship according to just two criteria: winning or losing. But the most important form of distrust Trump has cultivated over the past decade is the suspicion and hostility Americans feel toward each other. He took historically high levels of political polarization and sent them rocketing upward even more.

Trump’s first inaugural address in 2017 was unlike any other speech by an American president. It did not present the United States as a “shining city upon a hill”—Ronald Reagan’s parting words as he left office. It didn’t offer uplift or unity. It presented the United States as a wasteland in a rapid state of degeneration, caused by Trump’s political enemies. “For too long,” Trump said, “a small group in our nation’s capital has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the cost.” This was a theme throughout the speech—that nefarious and corrupt forces in the government had betrayed the public trust, and only Trump could restore it.

Trump was elected a second time on an even darker vision of the United States. He told Americans that their legal system is irredeemably corrupt. He declared that American democracy is a sham—except when he wins, of course—and described the country as a “third-world dictatorship.” He said immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country.” He presented a paranoid and apocalyptic vision of Manichean struggle in the United States: “Either the deep state destroys America,” he declared, “or we destroy the deep state.” He vowed that a revenge purge of the U.S. government would be at the heart of his second term. Most importantly, Trump said the “enemy from within”—Americans who oppose him—is a graver threat to the country than Russia, China, or any geopolitical adversary. He wanted Americans to fear and loathe their fellow citizens, and he got his wish.

Distrust and dishonesty are the wellsprings of Trump’s power. The ability to lie on an industrial scale without compunction gives Trump a significant advantage over political rivals who know they will be held to a different standard if they’re caught bending the truth. He has conditioned a significant proportion of the country to believe everything he says, or at least to forgive even the most blatant lies as somehow directionally true, mere trolling, or part of an elaborate plan to manipulate his political foes. We have a whole new political lexicon to describe this shift: alternative facts, seriously but not literally, flooding the zone with shit.

This project has enabled Trump to rewrite history. The most startling example of this revisionism is Trump’s insistence that the insurrectionists on January 6 were hostages and political prisoners. Even Trump’s strongest critics didn’t imagine that he would pardon every January 6 insurrectionist, including those who organized the assault on the Capitol and attacked police officers. Trump recently met with former Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio at Mar-a-Lago, who praised him for waiving his 22-year prison sentence. “I thanked him for giving me life back,” Tarrio posted on social media. “He replied with…I Love You guys.” Trump has described January 6 as a “day of love.”

Meanwhile, Trump insists that the public servants who did their jobs and declared the 2020 election legitimate—along with members of Congress who investigated him for attempting to steal the election and for his dereliction of duty on January 6—are dangerous subversives who must be punished. On April 9, Trump issued an executive order accusing former CISA director Christopher Krebs of being a “significant bad-faith actor who weaponized and abused his Government authority.” The order declares that Krebs “falsely and baselessly denied that the 2020 election was rigged and stolen.”

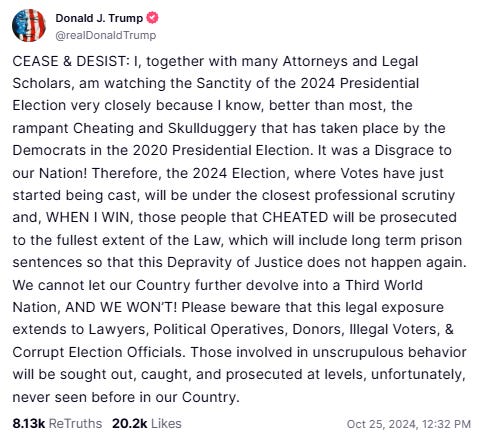

Trump is using the power of the state to go after individual Americans like Krebs, who was forced to quit his job at the cybersecurity firm SentinelOne after the administration revoked his security clearance (and suspended the company’s). When Krebs’ Global Entry travel clearance was rescinded, a DHS spokesperson said he is “under active investigation by law enforcement agencies.” Trump has argued that members of the January 6 committee should be prosecuted, along with “Lawyers, Political Operatives, Donors, Illegal Voters, & Corrupt Election Officials.” Trump faced prosecution in two cases over his attempt to overturn the 2020 election, and he knew he wouldn’t have to prevail legally if he could prevail politically. This meant going beyond Big Lie about the “stolen” 2020 election—he also had to convince voters that he was the victim of partisan “lawfare,” that the deep state was still colluding against him, and that the Democrats are actually the most urgent threat to American democracy. Or at the very least, he had to muddy the discourse sufficiently to get Americans to stop caring about his attempted coup.

After Trump’s attempt to overthrow the 2020 election reached its climax on January 6, it looked as if his political career was over. But Trump’s historical revisionism worked, and by returning him to the White House, American voters gave him a sense of political invulnerability that he never had before. Trump and his acolytes often refer to his victory as the greatest political comeback in history. Some Americans believe the hand of providence was at work. Trump touts his modest electoral victory—his popular vote margin was smaller than Bush’s in 2004, Obama’s in 2008 and 2012, and Biden’s in 2020—as an “unprecedented and powerful mandate.” Trump is behaving as if he really believes this. He has surrounded himself with loyalists like Bondi who have unleashed his most destructive impulses. He has followed through on the implementation of disastrous policies that he was restrained from enacting in his first term—such as the global tariffs. His corruption is orders of magnitude greater and he’s making no effort to hide it.

Most alarmingly, Trump is tenaciously pursuing the “retribution” he promised his supporters during the campaign. He’s going after law firms who were involved in actions against him, media companies, universities, and large swaths of the federal government. Many of these institutions have already submitted to Trump. Law firms are providing hundreds of millions in pro bono work, media companies like ABC and Disney have settled frivolous lawsuits (and it looks like CBS parent Paramount will soon follow), and Columbia University struck a deal with Trump in March.2

When it became clear that the Trump administration was deporting people to a Salvadoran dungeon on the basis of superficial criteria like tattoos or clothing, the administration’s response to journalists, judges, and members of Congress who demanded evidence and due process was “trust us.” This is the central command of Trump’s authoritarian presidency—distrust everyone except the leader and his apparatchiks. Immediately before markets plunged due to Trump’s arbitrary imposition of massive tariffs on nearly every country, House Speaker Mike Johnson said, “You have to trust the president’s instincts on the economy, okay? … This isn’t blind faith.” As global equity markets panicked, the value of the dollar tanked, and a sell-off of U.S. debt rattled the bond market, Republican members of Congress and administration officials repeated this claim like a mantra: trust the president.

Then Trump reversed course and reduced the tariffs, and his mouthpieces once again dutifully told Americans to trust him. If Trump keeps tariffs in place as part of an economically illiterate and quixotic plan to revitalize American manufacturing and eliminate trade deficits—even if this means dragging the United States into a recession—trust him. If he removes tariffs as part of ongoing negotiations—even if this means undermining faith in the United States’ global economic stewardship for imaginary gains—trust him. Trump’s policies and statements can be perfectly contradictory from one day to the next, and MAGA remains faithful.

But Trump has done nothing to earn Americans’ trust in his first 100 days in office. He has shown contempt for the rule of law and the separation of powers. He has thrown the strong economy he inherited into turmoil. In his desperation to meet the absurd deportation quota he set during the campaign, he has trampled on due process. He has empowered Musk and a group of twenty-something interns to unilaterally slash government programs without understanding what they do and destroy entire agencies. He has capitulated to Vladimir Putin over and over again, and he’s now threatening to walk away from Ukraine negotiations altogether (he promised to end the war in 24 hours during the campaign). He has alienated the United States’ closest allies by declaring his intention to annex Greenland, endlessly talking about turning Canada into the 51st state, and erecting pointless trade barriers.

Trump has also profited directly from the presidency in ways that were once unthinkable. He sells access to top investors in his meme coin. He has enacted crypto policies that directly benefit a company in which the Trump family has a deep financial interest (World Liberty Financial). His administration suspended an investigation into Justin Sun, a major investor in World Liberty. It’s no wonder that Trump fired 17 inspectors general immediately after taking office. Nor is it any surprise that his anti-anti-corruption efforts have included disbanding the National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team, as well as suspending the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and Corporate Transparency Act.

Perhaps the spectacle of an increasingly authoritarian president abusing his power and using the presidency as a vehicle for personal wealth creation—while ushering in an era of stagflation and economic chaos for the rest of the country—will be enough to convince Americans that MAGA is the disaster its critics always warned it would be. But what does it say about the health of the United States’ civic culture that Americans elevated Trump to the White House once again in 2024?

One of my biggest political miscalculations was my conviction that the Democrats should emphasize Trump’s assault on American democracy in the 2024 election, a case I made here, here, and here. While democracy was one of the most salient issues to voters—it ranked second only to the economy in a Gallup survey in September 2024—there was a partisan split on which party represented the most serious threat to democracy.

Trump somehow managed to convince millions of voters that his own legal troubles and the suppression of the Hunter Biden laptop story were more urgent democratic crises than a president who tried to overthrow an election. My mistake was assuming that voters would have a longer memory for attempted coups in the United States. I didn’t think Trump would be able to deflect from his scheme to send fake electors to Washington and disenfranchise voters, his pressure campaign against election officials (like his order to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find” him 11,780 votes), or the endless lawsuits he filed to throw out the election results.

But I was wrong. Trump shattered the most sacred norm in American democracy—the peaceful transfer of power—but in the febrile atmosphere of paranoia and partisanship that he has created, it was easy to convince voters not to trust what was right in front of their eyes. While most Americans were horrified immediately after January 6, partisan propaganda steadily did its work on the right. In March 2021, 79 percent of Republicans said law enforcement officials should find and prosecute the January 6 rioters—a proportion that fell to 57 percent in just six months. In March 2023, Tucker Carlson published footage from inside the Capitol and declared: “Taken as a whole, the video record does not support the claim that January 6 was an insurrection. In fact, it demolishes that claim.” Carlson argued that a tiny proportion of the rioters were “hooligans,” but the rest were “peaceful, they were orderly and meek. These were not insurrectionists, they were sightseers.”

Trump announced his 2024 campaign in Waco, Texas (suggestively) that same month and took the stage to a recording of the Star-Spangled Banner performed by the “J6 Choir”—inmates who had been imprisoned for their actions on January 6. The transformation from dangerous criminals to MAGA martyrs was complete. In the pre-Trump era, none of this would have been imaginable. When Al Gore lost to Bush in 2000 possibly due to a few hanging chads in Florida—a much closer result than Trump’s defeat in 2020—he conceded. There were no Gore-Lieberman flags fluttering in the teargas outside the Capitol or Democrats assaulting police officers. It would be bad enough if Americans simply memory-holed Trump’s attempted coup, but it’s much worse than that—they elected him even though he repeated his lies about the “rigged” election constantly, honored the criminals of January 6, and promised to seek revenge from those who attempted to hold him accountable for his coup.

In 1995, the political scientist Francis Fukuyama published Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. Fukuyama argues that a “nation’s well-being, as well as its ability to compete, is conditioned by a single, pervasive cultural characteristic: the level of trust inherent in the society.” Fukuyama defines trust as the “expectation that arises within a community of regular, honest, and cooperative behavior,” and he observes that the United States is a “high-trust” society.

A core theme of Trust is the importance of culture in driving economic and political outcomes. For hundreds of years, America’s democratic culture has been a defining characteristic and one of the main sources of the country’s success. This is the aspect of American civil society that so impressed Alexis de Tocqueville—the profusion of voluntary associations in the country required large amounts of social capital, which can only be sustained by shared norms and values. Fukuyama argues that democracy is so ingrained in American culture that citizens take it for granted:

Many Americans could give a reasonable account of why democracy is preferable to tyranny, or why the private sector can do things better than “big government,” based on either their own experience or the persuasiveness of broader political and economic ideologies they absorb as part of their general upbringing. On the other hand, it is certainly the case that many Americans adopt such attitudes without thinking much about them and pass them on to their children, so to speak, with their toilet training.

There were early cracks in the foundation of America’s culture of trust in the mid-1990s. The political scientist Robert D. Putnam published an essay titled “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital” in 1995, which he developed into an influential book with the same title. Putnam observed that levels of social capital had been declining in the United States for decades, which was reflected in lower levels of community engagement, political participation, and social trust. Fukuyama cites Putnam and acknowledges a “vast increase in the general level of distrust.”

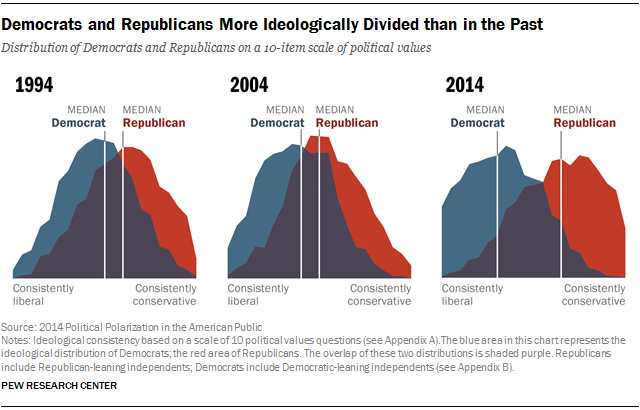

The mid-1990s inaugurated a period of surging polarization in the United States. While just 16 percent of Democrats regarded Republicans “very unfavorably” in 1994, this proportion jumped to 38 percent by 2014. Republicans’ very unfavorable views of Democrats spiked from 17 percent to 43 percent over the same period. In 1994, 64 percent of Republicans were more consistently conservative than the median Democrat and 70 percent of Democrats were more liberal than the median Republican—proportions that shot up to 92 percent and 94 percent, respectively, by 2014. These dramatic shifts took place just in time for the rise of Trump, one of the most divisive presidents in American history.

The era of Trumpism has coincided with tectonic shifts in the media landscape—beyond increasingly partisan mainstream outlets, there has been an explosion of low-information podcasts and alternative outlets that feed conspiracism and institutional distrust on a vast scale. The do-your-own-research, just-asking-questions brand of information dissemination is inherently hostile toward expertise and established institutions—from newspapers to universities to government. This is a media environment in which Trump thrives, as his core message is that the establishment is not to be trusted, and most existing institutions are definitionally part of the establishment. It’s no wonder that there has been a great contraction in trust in institutions in recent decades—Gallup reports that average confidence in major institutions (such as the military, the Supreme Court, Congress, public schools, and media organizations) has collapsed from 43 percent in 2004 to just 28 percent in 2024.

But the most alarming development is Americans’ declining faith in democracy itself. While 52 percent of Americans said they were satisfied with how democracy was working in 1998, this proportion has fallen to 28 percent. In October 2024, over three-quarters of Americans said they believed democracy was under threat, while nearly 60 percent said they thought Trump would use the DOJ to prosecute his political opponents. Yet Trump still gained ground with nearly every major voting demographic, swept the battleground states, and became the first Republican presidential candidate to win the popular vote in two decades. It’s possible that Americans were willing to overlook Trump’s authoritarian ambitions and his past anti-democratic behavior because they no longer have trust in democracy. This is an outcome Fukuyama, Putnam, and anyone else concerned about declining social trust in the 1990s would have found it difficult to imagine. Americans have become so distrustful of their democratic system that they were willing to elect a president who is explicitly hostile toward democracy.

However, Fukuyama makes an observation in Trust that anticipated this development: “While the American founding was highly self-conscious and rational,” he writes, “subsequent generations of Americans accepted the principles of the founding not because they gave them the same conscious consideration as the Founding Fathers but because they were traditional.” In other words, Americans’ trust in democracy became more of a reflex—or even a dogma—than an informed view. While the Founders understood what it meant to live under an undemocratic system, contemporary Americans have no such experience. This has made them complacent about their democracy, which is why they were willing to risk returning an anti-democratic demagogue to power because he promised to make groceries cheaper.

Now Americans are realizing that they will get authoritarianism as well as incompetence and higher grocery prices. This could be enough to turn them against Trumpism and hand the Democrats electoral victories in 2026 and 2028. But even if this turns out to be the case, the crisis of trust will remain. Until Americans recognize that the only non-negotiable position is respect for democracy and strict fidelity to the rule of law, future demagogues will be standing by to exploit the trust crisis in their own ways. No matter how frustrated voters become with American democracy, the solution should never be the elevation of a would-be autocrat who exploits social and political distrust instead of figuring out ways to make Americans trust their system—and each other—once again.

Trump became a mainstream political figure by asserting that President Obama wasn’t born in the United States. “Birtherism” in the Tea Party was a clear precursor to the prejudice and paranoia of the MAGA movement.

Other elite schools, such as Harvard and Princeton, are pushing back.