Bracing for the postliberal international order

Do critics of the liberal international order have any alternatives in mind?

Noam Chomsky and Nathan Robinson recently published a book called The Myth of American Idealism: How U.S. Foreign Policy Endangers the World. It’s largely an introduction to the Chomskian worldview—Chomsky and Robinson spend hundreds of pages chronicling atrocities committed or enabled by the United States and conclude that the only way to save the world (really) is for American citizens to rise up and end their government’s quest for global domination. This is an argument Chomsky has been making for about sixty years.

The main theme of The Myth of American Idealism is the idea that the United States doesn’t stand for any values that transcend rapacious imperial interests. Chomsky and Robinson argue that the emphasis on values like democracy and human rights among American policymakers—the current administration notwithstanding—is nothing but a rhetorical smokescreen for the motivations that have always driven great empires and states: power and wealth. Some of their observations about American foreign policy are fair, such as their criticism of the United States’ support for dictators, the horrors of the Vietnam War, and the Cold War campaigns of violence and subversion in Central and South America. But the only way to summarize the past 80 years of American foreign policy as one long period of imperial violence and coercion is to ignore an entire library of facts that are inconvenient for that thesis.

Consider the Marshall Plan, for instance. The United States spent nearly $180 billion (adjusted for inflation) to rebuild Europe after World War II. After the severely putative conditions of the Treaty of Versailles helped create the conditions for the rise of fascism and another global war, American policymakers knew that stability and prosperity were more important than retribution. A cynical interpretation of this policy would be that the United States laid the foundation for 80 years of global economic, political, and military hegemony. A fair interpretation would be that the United States wanted to construct a liberal international order that would give free countries powerful incentives to join institutions that offered collective benefits—from mutual defense to open economic exchange. The United States pursued its interests, but those interests were underpinned by the value-based assumption that political and economic freedom would ultimately be good for everyone.

When the USSR collapsed, former Soviet states immediately lined up to enter the Western sphere of influence. Many of those countries have become thriving, integrated democracies in the decades since they were liberated from Soviet rule. The democracies of Eastern Europe have repeatedly elected to retain their membership in this system, and the ones that were left out—such as Ukraine—have spent many years trying to join. Ukraine is now fighting to maintain its sovereignty in the face of an imperial war launched by Vladimir Putin’s Russia, the last gasp of the Soviet system that was defeated by the West three and a half decades ago. Ukraine wants to be part of the West, and Putin won’t allow it. This is because he knows his kleptocratic petro-dictatorship isn’t a political or economic model that any free people want to emulate. The only way for Russia to retain its sphere of influence—and for Putin to suppress any domestic opposition—is through force.

Chomsky and Robinson would argue that this brief history of postwar U.S. foreign policy is naive and self-serving. They believe the United States and the Soviet Union were morally indistinguishable—two power-hungry empires that used each other as political foils to justify their respective quests for world domination. Similarly, they believe the U.S.-led international order today is merely American imperialism with better branding—all the United States’ talk of liberal values like democracy cloaks the same acquisitive impulses great powers have always had. On this view, nothing has fundamentally changed in the international system in millennia. Relationships between states in the year 2025 are exactly the same as they were when Thucydides wrote his History of the Peloponnesian War in the Fifth Century BC. “The strong do what they can,” Thucydides wrote, “and the weak suffer what they must.”

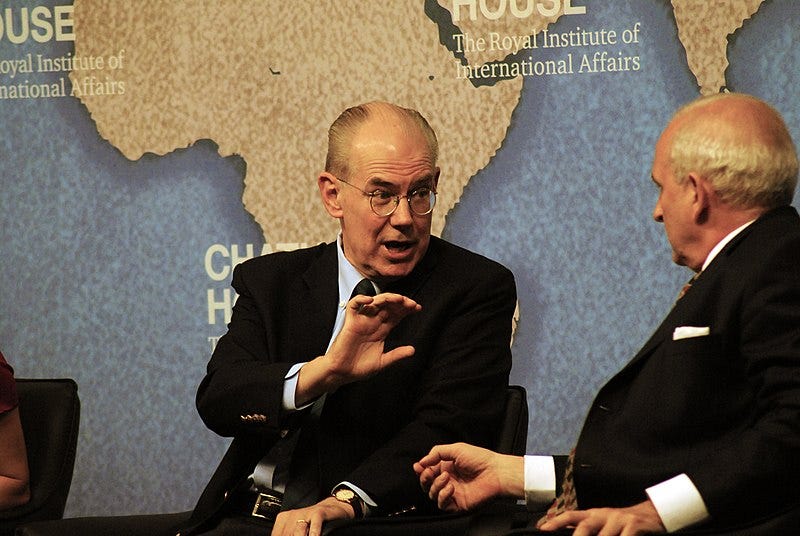

This is a view shared by international relations “realists” such as Harvard’s Stephen Walt and the University of Chicago’s John Mearsheimer, both of whom are cited approvingly by Chomsky and Robinson. Walt returned the favor with a review of The Myth of American Idealism in Foreign Policy Magazine titled “Noam Chomsky Has Been Proved Right,” in which he largely agrees with Chomsky about the United States’ “costly and inhumane approach to the rest of the world, an approach he [Chomsky] believes has harmed millions and is contrary to the United States’ professed values.” Mearsheimer has been a leading critic of post-Cold War U.S. foreign policy, which he argues has strayed from realist principles by pursuing goals like democratization and the spread of liberalism instead of focusing on the hardheaded pursuit of a global balance of power. Realists believe there is no role for values or ideology in international relations, arguing instead that state behavior is determined by the distribution of power in the international system. To realists, state behavior is governed by mindless physical forces—a process Mearsheimer likens to billiard balls smashing against one another.

The overlap between realists and anti-American leftists1 like Chomsky and Robinson is awkward. For example, in his 2018 book The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of U.S. Primacy, Walt argues that the United States’ support for Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq War was a prime example of a cherished realist strategy—“offshore balancing”—in which the United States ensures that no single power can become dominant in its own region. Walt writes that the Reagan administration “helped thwart an Iranian victory in the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88) by giving Saddam Hussein military intelligence and other forms of assistance,” which he cites as an example of the “reassuring history” of the strategy. Chomsky and Robinson rightly cite the United States’ support for Saddam Hussein as an ugly example of Washington’s indifference to the titanic human cost of its actions.

A central difference between anti-American leftists and realists is how they view the interplay between descriptive and prescriptive claims about international relations. A core theme of The Myth of American Idealism is that the United States has the same motivations as any other great power. While American policymakers claim to pursue higher ideals, they’re just as greedy and power mad as the other empire builders throughout history. This belief is shared by realists—just as physical forces are eternally unchanging, the relationships between countries will always be driven by the same dynamics (i.e., the desire to maximize a state’s relative power). But when it comes to the prescriptive element of state behavior, realists and anti-American leftists diverge. Chomsky and Robinson clearly believe it is possible for the United States to adopt a foreign policy that aligns with their moral principles—making the case for this shift is the whole purpose of their book. But realists don’t believe such a shift is conceivable—state behavior will always be determined by the character of the international system, which is anarchic and unchanging.2

There is a fundamental contradiction at the heart of the realist critique of U.S. foreign policy: it cannot simultaneously be true that state behavior is always governed by realist principles, but the United States deserves criticism for deviating from those principles. While Chomsky and Robinson are wrong to claim that the United States is no different from imperial powers throughout history, there’s no logical inconsistency in their argument. Unlike realists such as Mearsheimer, they also believe moral and political progress is possible—a view that is supported by the overwhelming weight of historical evidence.

While the anti-American left presents some valid critiques of postwar U.S. foreign policy, its descriptive claims about the liberal international order have always been wrong. The idea that the Western system of alliances, economic partnerships, and political arrangements is morally equivalent to the backward and tyrannical Soviet system that kept hundreds of millions of people trapped behind the Iron Curtain for nearly half a century is ludicrous. What is the NATO version of the Gulag system? Institutions like NATO and the EU haven’t been riveted upon oppressed peoples who had no say in the matter—they have been freely chosen by democratic countries. There is no starker evidence of this fact than the overwhelming support in Ukraine for integration with the West—a demand that could only be thwarted by the largest conflict in Europe since World War II.

Chomsky and Robinson insist that the United States is the most dangerous force on the planet, but the dozens of countries that have aligned themselves with America for 80 years don’t appear to think so. In fact, the United States’ allies are now far more concerned about the Trump administration’s plans to abandon the liberal international order than they ever were about the exercise of American power (yes, I remember the European opposition to the Iraq War). Over the next several years, we’re going to witness a geopolitical experiment. As the United States withdraws from institutions like NATO and diminishes its role in global security arrangements, we’ll see if the result is a safer, freer, and more stable world.

Realists and anti-American leftists are nearly indistinguishable when it comes to one of the great geopolitical crises of our time: Russia’s war on Ukraine. For example, both groups blame NATO expansion for the invasion, despite the fact that the war was the surest way for Moscow to convince other European countries to join the alliance (which Finland and Sweden promptly did). They both ignore Putin’s main motivation for launching the war—the destruction of Ukraine as a sovereign nation and the expansion of Russia’s sphere of influence—preferring instead to present his war of state extermination as an outgrowth of perfectly reasonable security concerns. And they both believe capitulating to Putin’s demands (about permanent Ukrainian neutrality, for instance) is necessary to bring the war to an end.

There’s another group that shares each of these convictions and misconceptions: Trump’s America First movement. Since taking office, Trump has suspended American military aid and intelligence sharing with Ukraine. He condemns Volodymyr Zelensky, not Putin, as a dictator. He demands the rights to $500 billion of Ukraine’s natural resources as payment for support the previous administration provided, and he refuses to offer any concrete security guarantees in exchange. Trump accuses Zelensky of risking World War III but declares that Putin is eager to pursue peace. None of this should come as a surprise—Trump has long condemned the United States’ support for Ukraine as fuel for a pointless “proxy war,” while Vice President J.D. Vance once said “I don’t really care what happens to Ukraine.”

There are significant political differences between realists, anti-American leftists, and the MAGA movement. For example, Walt, Mearsheimer, Chomsky, and Robinson are all extremely critical of the United States’ support for Israel, while Trump often boasts about being the most pro-Israel American president in history. Anti-American leftists often sound exactly like Trump when it comes to NATO and Ukraine, but his plan to ethnically cleanse and “take over” Gaza is rightly anathema to them. However, this doesn’t change the fact that Trump is trying to build an international system that more closely aligns with the one realists and anti-American leftists advocate than the one defended by the foreign policy “establishment” all three groups despise.

Trump believes the United States should stop defending Europe. He has consistently expressed a desire to withdraw from NATO, and the United States’ allies have every reason to believe this is a serious possibility in the coming years. In one sense, the Article V collective defense provision has already been fatally undermined—nobody really expects that Trump would send U.S. forces to protect, say, one of the Baltic states in the event of a Russian invasion. Other NATO allies would be far less inclined to offer their support without an American backstop.

While it may seem like a withdrawal from Europe could mean greater support for allies in East Asia—this is what Mearsheimer thinks the Trump administration is moving toward—Trump has a long history of treating Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan with the same contempt he directs toward Europe. He routinely demands that each of these countries drastically increase defense spending and threatens to withdraw troops if they fail to comply. For example, he says Taiwan should spend 10 percent of its GDP on defense—a ridiculous and politically impossible target, and about three times what the United States spends proportionally. He has always insisted that American military support in East Asia is contingent on allies meeting these unreasonable and capricious demands. He says allies should treat the United States like an “insurance company” that’s liable to raise rates or drop coverage for no particular reason.3

In the Myth of American Idealism, Chomsky and Robinson write: “In the 1990s, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the purpose of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) became unclear.” In an August 1990 essay, Mearsheimer predicted that NATO would disband without the common Soviet threat holding it together. He also made a series of other predictions that never came to pass—like the idea that Germany would suddenly become an aggressive regional hegemon that would menace and potentially invade its neighbors. Instead of falling apart, NATO rapidly expanded throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Walt, Mearsheimer, Chomsky, and Robinson regard this as a fateful mistake.

After Putin invaded Ukraine, Mearsheimer declared that “The West, and especially America, is principally responsible.” Mearsheimer often asserts that the “taproot” of the conflict is NATO expansion. Walt makes a similar argument, blaming the war on “liberal illusions” about bringing Ukraine into the Western political, economic, and military order. Chomsky and Robinson claim that NATO is guilty of antagonizing Russia, and they believe the expansion of the alliance is one of the main reasons for the war. They cite one of the most common canards about NATO expansion—that Secretary of State James Baker promised Mikhail Gorbachev the alliance wouldn’t move “one inch” to the east after German reunification at the end of the Cold War. Aside from the fact that this was never official U.S. policy, it’s a strange argument for self-styled anti-imperialists to make—what sort of radical believes a handshake deal between two great powers should be a binding contract that permanently determines the fate of Europe? Doesn’t that sound like the sort of imperial carve-up Chomsky and Robinson claim to oppose?

Chomsky and Robinson care about sovereignty and self-determination when it comes to the United States’ involvement in Central and South America or the Middle East, but they suddenly don’t care about it in the context of Russia’s campaigns of aggression and subversion in Eastern Europe. The reason is simple: they’re reflexively hostile to the United States, even when it defends their stated values. In Europe, the United States protects independent democracies from Russian encroachment, but Chomsky and Robinson invert this argument—it’s Russia that is under threat. European countries freely chose to join the Western system of political, economic, and military cooperation instead of remaining shackled to Putin’s crumbling petro-autocracy until the end of time, and Chomsky and Robinson regard this as intolerable. It’s no surprise that realists would be perfectly happy with this status quo—their theory is amoral—but Chomsky and Robinson’s support for it is plain hypocrisy.

Just as Mearsheimer made the absurd argument that Germany would pose a military threat to its neighbors after the Cold War, Chomsky and Robinson believe Putin had legitimate reasons to fear a NATO-supported attack on Russia from Ukraine. They accept Moscow’s stated reasons for the invasion whenever those reasons align with their political narrative (hostility toward NATO expansion), and they don’t bother mentioning the reasons that run counter to that narrative—such as Putin’s exhaustively documented insistence that Ukraine is an artificial country that should be reintegrated into Russia. Mearsheimer takes this denialism a step further, declaring that there’s “absolutely no evidence” that “Ukraine is a country that he [Putin] wants to conquer and incorporate into Russia.” Mearsheimer must have missed the march on Kyiv.4

The clearest thread linking anti-American leftists, realists, and Trumpists is that they all deflect blame from Putin. Trump has accused NATO and even Zelensky of starting the war. His political reasons for doing so are obvious—he wants to cut off support for Kyiv, so presenting Zelensky as a corrupt dictator and warmonger makes doing so more politically palatable to his supporters. But there’s something deeper driving Trump’s hostility toward Ukraine, NATO, and the entire Western alliance. As I have written elsewhere, he no longer wants to be constrained by the rules and norms of the international system that the United States constructed after World War II. He wants to build a world in which he can sit down at a cartoonishly long table with Putin and iron out a deal on Ukraine without worrying about what Europe or even Kyiv thinks. After “we straighten it all out” in Ukraine and the Middle East, as Trump puts it, he wants to negotiate a deal with Moscow and Beijing to cut defense spending in half.

These are grandiose delusions, of course. Trump believes his abandonment of Ukraine will make China less likely to invade Taiwan, but it will have the opposite effect. Putin hasn’t shown any sign that he will settle for less than the destruction of Ukraine as a viable independent state, and Trump has given away all his leverage in advance. Trump is attacking and alienating America’s closest allies and trading partners at every available opportunity—from launching trade wars against Canada, Mexico, and Europe to leaving the Europeans out of Ukraine negotiations. He wants to withdraw from NATO while threatening military aggression (against Panama and Greenland, for instance) in the Western hemisphere. He wants to restore an era of rapacious imperialism and mercantilism. There’s only one possible explanation for all this: he wants to destroy the liberal international order.

All those who have spent many years arguing that the U.S.-led international order is either a failure (Walt and Mearsheimer) or an imperialist monstrosity (Chomsky and Robinson) now have a question to answer: what should take its place?

Walt and Mearsheimer have long argued that NATO expansion was a “fateful error.”5 Just a few days ago, Mearsheimer said the “cause of these wars was NATO expansion—not Putin’s supposed imperialism.” He also says, “Five years from now, I’m not even sure there will be a meaningful Article 5 guarantee left.” Confronted with this monumental transformation of the global security order, Mearsheimer argues that America should “keep military forces in Europe as long as the Europeans don’t trade with China in ways which are detrimental to the United States.” Meanwhile, Walt says that there’s “no question that Europe should be more responsible for its own defense,” though he thinks the United States’ shift away from the continent should take place over the course of five to ten years.

These are strange positions for realists to hold—if it’s true that the balance of power is the only variable that really matters in the international system, why should the United States withdraw from Europe when it serves as an effective check on Russian aggression? Why should realists want a return to the era of multipolar competition in Europe? And shouldn’t this decision be based on securing the right balance of power instead of some Trumpian deal regarding European cooperation with China? Many of Europe’s economic interests already align with the United States—Europeans want to de-risk supply chains with less reliance on Chinese manufacturing, they’re concerned about intellectual property theft and other unfair trade practices, and they don’t want to give China an edge in critical industries like AI and quantum computing. It’s strange to hold the transatlantic alliance hostage on the basis of European trade policy toward China, particularly for a realist. The balance of power enabled by this alliance either makes sense on realist logic or it doesn’t.

The aforementioned essay Mearsheimer published in 1990 was titled “Why We Will Soon Miss the Cold War.” He argued that the “Soviet threat provides the glue that holds NATO together.” In the absence of this consolidating threat, Europe would plunge back into the “untamed anarchy” of the multipolar system that existed in the first half of the twentieth century. He imagined “scenarios in which Germany uses force against Poland, Czechoslovakia, or even Austria.” He thought Germany would acquire nuclear weapons. He argued that Russia might even be forced to check Germany’s territorial ambitions. Mearsheimer also thought Eastern European states would acquire nuclear weapons. He was exactly wrong about all the above—while realism predicted a breakup of the post-World War II security order in the absence of the Soviet threat, that order drastically expanded instead. Instead of becoming an aggressive regional hegemon, Germany became the anchor of the EU.

Mearsheimer’s outlook for European security and stability at the end of the Cold War was grim: the “United States is likely to abandon the Continent; the defensive alliance it has headed for forty years may well then disintegrate, bringing an end to the bipolar order that has kept the peace of Europe for the past forty-five years.” However, the transatlantic security order became even stronger after the Cold War. One would expect Mearsheimer to celebrate this fact given his conviction that this order was the only thing preventing a return of dangerous multipolarity in Europe—a source of constant warfare over the centuries. But Mearsheimer has instead spent decades attacking NATO for expanding.

For a realist, doesn’t it matter that war between Western European powers like France and Germany is almost inconceivable? Doesn’t it matter that countries like Germany and Japan are now major Western allies? Doesn’t it matter that the American security umbrella in Europe and East Asia has worked better than anyone could have imagined at the end of World War II? Despite these historically unprecedented successes, Walt and Mearsheimer have relentlessly criticized the postwar security order.

Now that Trump is contemplating an American withdrawal from Europe, Mearsheimer is back to making dire predictions. He says (correctly this time) the transatlantic alliance is in “deep trouble.” He suspects that Article V will be dead within five years. When he was recently asked about the possibility of Germany acquiring nuclear weapons, he said “there’s a high likelihood” that it will do so. Now that the “American pacifier is leaving Europe,” he argues, “powerful centrifugal forces that exist in Europe will begin to manifest themselves.” In other words, great power competition will return.

To some extent, Mearsheimer understands the cost of the Trump administration’s deconstruction of the liberal international order. He says, “It was the presence of the United States, which provided security in the form of NATO that allowed the EU to flourish. When the European Union won the Nobel Peace Prize, I considered this a fundamental mistake. NATO should have won the peace prize.” Given the realist logic behind the American security umbrella that has prevented the resurgence of dangerous multipolarity in Europe, it’s unclear why Walt believes the United States “should be shifting its attention and resources elsewhere.” Or why Mearsheimer thinks the United States should go ahead and pull out if Europe doesn’t adopt America-friendly trade policies toward China.

Walt and Mearsheimer think the Western sphere of influence should be smaller to avoid antagonizing Russia. A reporter from Der Spiegel recently asked Mearsheimer: “If a majority of people in Ukraine want their country to join the EU or NATO, what gives you the right to deny them that wish?” Mearsheimer replied: “Russia is a great power, and it has made clear that it would rather destroy Ukraine before it will let that happen.” This is the dark heart of Walt and Mearsheimer’s argument about NATO expansion: they believe Russia should have a permanent veto over the political, economic, and security arrangements made by many European countries—not just Ukraine. This is the logical consequence of their view that NATO should not have expanded—if their advice had been heeded, the countries that are now part of the alliance would be forced to submit to Russian demands. In this sense, Walt and Mearsheimer should welcome Trump’s hostility toward NATO—if the goal is to avoid upsetting Russia, this is exactly what Trump’s plan for Europe will achieve.

At least realists acknowledge that the liberal international order has some value in countering great powers like Russia and China. Anti-American leftists like Chomsky and Robinson make no such acknowledgment—they view the entire postwar security architecture built and maintained by the United States as a vast imperialist machine designed to impose America’s will on the world. They have this backwards, of course—the American security umbrella is what protects the sovereignty of countries in Eastern Europe and East Asia from regional hegemons like Russia and China. But Chomsky and Robinson refuse to acknowledge this obvious fact, and they argue that a world without NATO and the rest of the Western alliance system would be much freer and safer. They cite the political scientist Richard Sakwa, who says, “NATO exists to manage risks created by its existence.” If there were no NATO, Russian aggression would magically disappear.

This argument runs counter to many decades of history, but it remains the galvanizing belief for a large swath of the Western left. However, until Trump came along, the prospect of the United States abandoning NATO or its East Asian allies always seemed comfortably remote. This allowed critics like Chomsky and Robinson to decry the horrors of Western imperialism safe in the knowledge that the alternative system they have long clamored for—a world without NATO and the other security arrangements of the liberal international order—would never be put to the test. Now that the Trump administration is working diligently to destroy the liberal international order, Chomsky and Robinson should start thinking seriously about the system that should replace it.

Presumably, this system would involve a dramatic reduction of American defense spending; the removal of American troops from Germany, South Korea, Japan, and many other countries; and the disbanding of “imperialist” institutions like NATO. Chomsky and Robinson may want to answer a few questions about this new world. For example, will the withdrawal of American forces from East Asia make a Chinese invasion of Taiwan more or less likely? Will North Korea be more or less aggressive toward South Korea if there are no American troops in the country? Will an American withdrawal from NATO increase or decrease the probability that Putin will invade one of the Baltic states? Will nuclear proliferation—a major focus in The Myth of American Idealism—accelerate or decelerate once the American nuclear umbrella over Europe and East Asia is folded up (which will give countries in those regions powerful incentives to build their own nuclear weapons)? If the United States slashes its military budget and hides behind its oceans, will Russia and China exploit the vacuum of power or suddenly decide that world peace would be nice?

For supporters of the liberal international order, the answers to these questions are clear. For those who want to destroy that order, the answers should be more disturbing than ever.

It’s difficult to find a term that effectively captures the Chomskian worldview. A term like “anti-imperialist” grants Chomsky’s premise, while words like “radical” or “progressive” are too vague to be helpful. “Anti-American” may sound unfair, but given the obsessive focus on the perceived crimes and malign influence of the United States in Chomsky’s worldview (which is shared by many on the left), it’s the most apt description.

Mearsheimer takes this view beyond international relations and argues that moral and political progress aren’t possible—a view I criticized here.

Realists and anti-American leftists have for many years argued that the United States should adopt a more restrained foreign policy. However, there are differences to note—realists are more focused on American power checking China, for instance. But the general critique of U.S. foreign policy since the Cold War—that it is overly expansionist and has unnecessarily antagonized other major powers like Russia—is shared by realists, anti-American leftists, and Trumpists alike.

To this day, after three years of devastating warfare, Mearsheimer insists that there’s “no evidence” Putin is an “imperialist who wants to conquer all of Ukraine and create a Greater Russia.” He appears to believe that the failure to capture more than about a fifth of Ukraine’s territory is all the proof he needs. But it’s clear that Putin would take more territory and decapitate the Ukrainian government if he could.

The words of George F. Kennan, a realist hero and the architect of the United States’ containment policy during the Cold War.

An excellent essay.

The likes of Mearsheimer and Chomsky excuse "great power" aggression by Russia, whatever their platitudes.

>Do critics of the liberal international order have any alternatives in mind?

Yes, it's called "not dying in a nuclear apocalypse so Ukraine can have a puppet government taking orders from Washington instead of Moscow. Details are kinda unimportant when dealing with an existential threat of that scale.